Maintaining Maximal Strength In Lockdown With The Exerfly: A Case Study With Mick Byers

Flywheels have become increasingly popular over the last couple of years, with more and more brands and versions available.

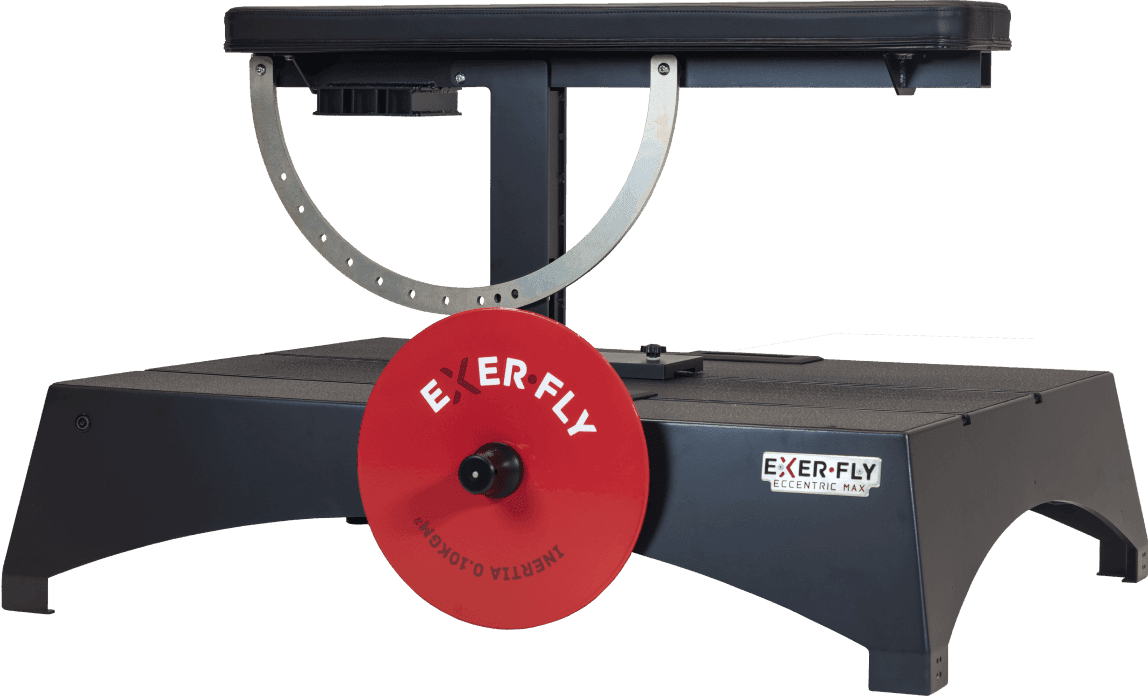

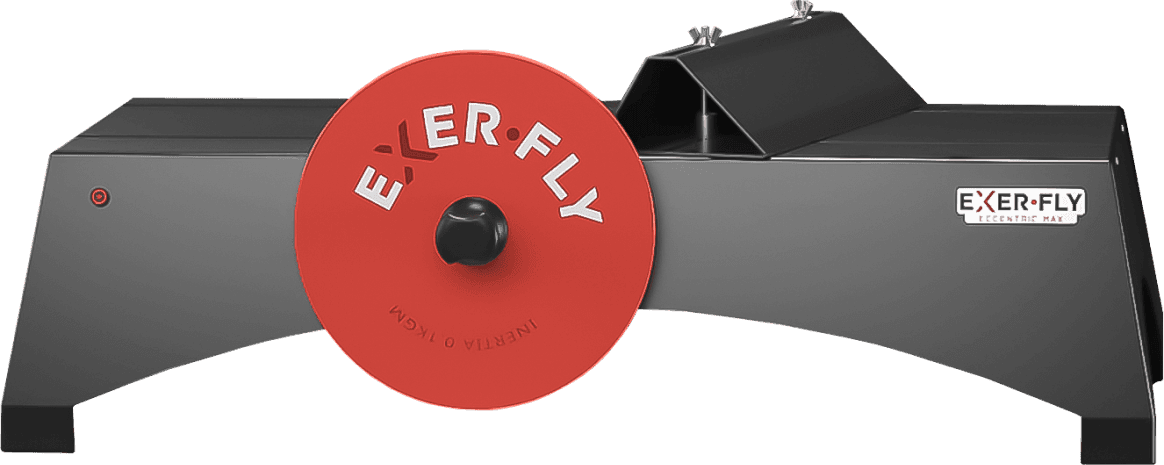

The popularity of flywheel exercise equipment in the last couple of years is no surprise to those lucky enough to have one – they're compact, portable, and have massive potential for creating eccentric overload.

Eccentric load is exerted on a muscle when it lengthens and plays an essential role in braking and managing forces. It also has the greatest capacity for force, so improvements in eccentric strength should lead to greater max strength.

One drawback with conventional weight training is that our ability to overload the eccentric phase is limited by our ability to apply concentric force – when the muscle is contracting or shortening in length.

Taking the back squat as an example, to complete a full rep, we must complete the concentric phase of the lift or return to a standing position. This weight will always be less than what we could control during the eccentric portion of the lift – or we get stuck in the bottom position and unable to return to standing.

There are methods to utilize eccentric overload, but they come with a high risk: reward ratio and need at least 1-2 people to help return the weight to its starting position each rep. Thus, they are difficult to justify and only suit limited environments.

Traditional strength training determines the eccentric load simply by the load. The weight at the top is the same as at the bottom. With a flywheel, it is determined by the size and speed that the flywheel achieves.

In practice, each size flywheel has a range of eccentric force outputs that can be achieved. As it slows down, the eccentric force also declines – making it possible to undergo high eccentric forces (when the wheel has speed) and then powerfully return to the starting position once eccentric force has dissipated to a suitable level.

This is known as variable resistance, highlighting how you only get back eccentrically the effort produced concentrically.

My Experience With Flywheel Training

Living in Sydney last year meant I was in various levels of lockdown throughout the year and worked with front-line workers. So I chose to restrict how I used my local gym even when it wasn’t closed.

A home gym would be the typical solution here. But not only was it almost impossible to get equipment, but I also didn't have the space or a suitable training area for it – especially once I decided that my family would be relocating from Australia to Ireland at the end of the year!

I had been eyeing a flywheel for a long time, so I decided to pull the trigger! Given the situation described, the small footprint, portability, and versatility made choosing the Exerfly over other models a no-brainer.

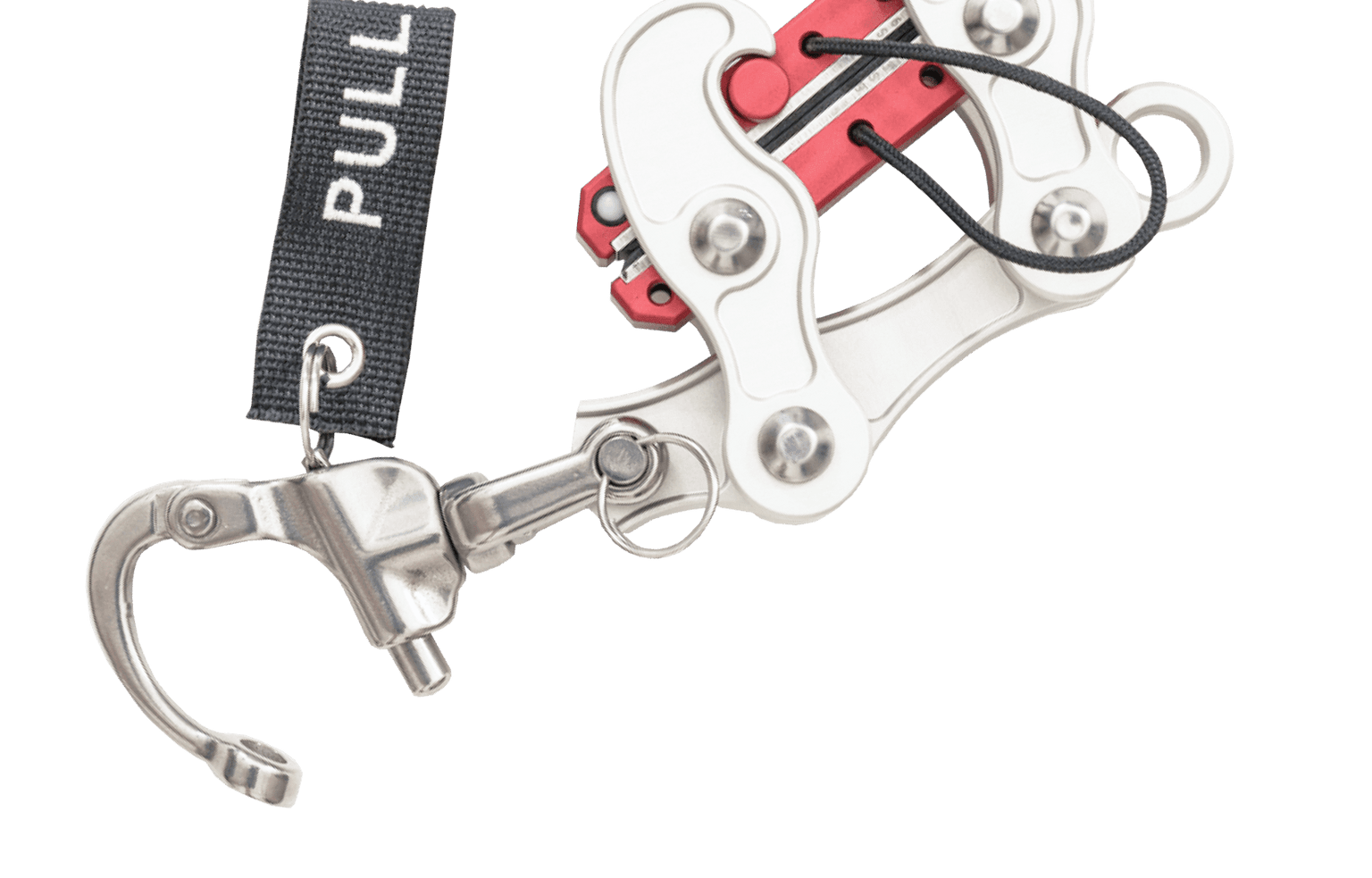

The platform, some flywheels, and several attachments were sent over in a shipping container, while the rack mount and remaining flywheels and attachments were in my suitcase for the flight.

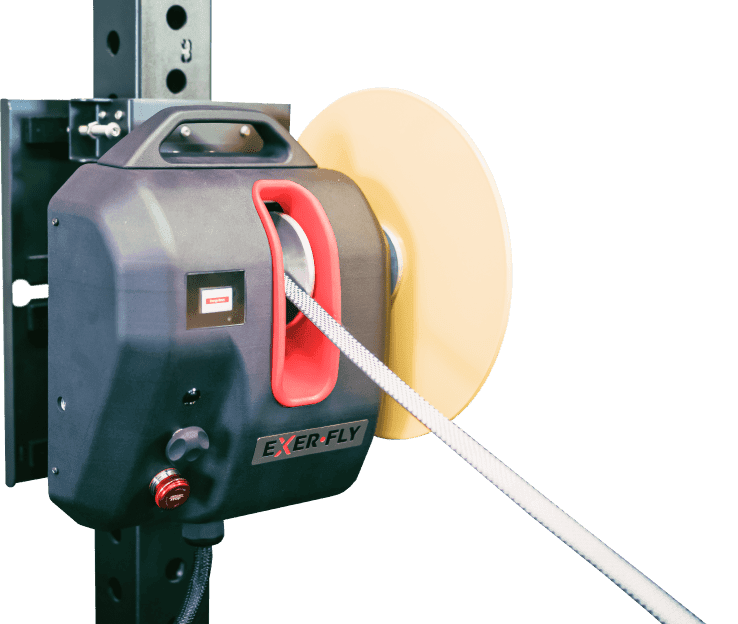

The rationale was that I would be able to utilize the rack mount immediately as my primary training device, and I could wait until our working and living situations were organized before joining a gym.

Training Timeline

- Sept-Oct 2021 (8 weeks) - Training with the Exerfly Platform focusing on lower body exercises and upper body rowing.

- Nov – end Dec 2021 (8 weeks) – No Exerfly. Departed for Ireland on 22 December.

- Jan – Feb 2022 (8 weeks) Exerfly Rack Mount with a focus on upper body push and pull, trunk rotation, rotator cuff, and hip strength. No gym access at the time.

- Mar 2022 – Return to a commercial gym.

Before departing for Ireland, I regularly squeezed in sporadic gym sessions and regularly completed 1-2 short speed sessions each week. I always had at least one 20kg dumbbell, some resistance bands, and somewhere to perform chin-ups and inverted rows variations.

At least 2, and often 3, sessions a week were completed with the Exerfly, except for November and December, when I didn't have a suitable place to mount the rack. I averaged 3 sessions per week from September to March, taking a break during the Christmas and New Year’s periods.

In general, each session contained 2-3 sequences of exercises, structured as follows:

- Exerfly flywheel exercise

- Jump or ballistic DB variation

- Accessory or Resilience exercise

Once in Ireland, I also used a ratchet strap for high-intensity (effort) isometrics like mid-thigh pull and modified hip bridge, and floor press exercises completed once per week.

Most sessions contained 3 sequences with 3-4 sets in each sequence. Sets with the Exerfly usually included 6-12 reps.

Returning to the Gym

Upon returning to the gym in March, I was surprised at how easy it was to get back into free weights – I felt strong, and any DOMS were minimal. It only took a few sessions before I was able to really push the intensity and test my strength levels.

There was no real change in strength for exercises like Single Leg RDL (DB) and Chin Ups, which I had been able to maintain with the amount of weight I had, or through the volume, I was able to perform.

What shocked me was how close my strength levels were to more 'pure' max strength exercises like the Deadlift (Trap Bar) and Bench Press (DB).

I was within 10-15kgs of my typical strength levels of close to 2x body weight for the deadlift. It wasn't so much that I didn't feel like I didn't have enough strength to do it, but the body just hadn't been exposed to that level of 'neural stress' in too long and went into protection mode. This was less noticeable for the bench press, and I was within 5kgs of my usual level.

While these were not 'true' 1RM tests, it is indicative of the real-world environment many of us work in and is reliable enough to determine that I experienced only minor losses in max strength when using only the Exerfly with maximal intensities.

Conclusions and Practical Applications

The biggest practical application I take from the experience is that using a flywheel device in the absence of other forms of heavy external load training (i.e., that which uses a Barbell or heavy DBs) is sufficient to at least maintain maximum strength levels.

While I could utilize a 20-24kg DB (depending on timeline), training sessions always involved high-intensity efforts and were supplemented by short duration, high-effort speed sessions (predominantly accelerations).

Physiologically, two critical drivers of max strength are the amount or rate of motor unit activation (or their combination). These two factors can be influenced by load and effort– which is why high-intensity jumps and speed efforts can improve max strength.

As both were regular elements of my training, how much max strength was maintained by the Exerfly or jump and sprint activities is hard to say. With that said, I'm not sure knowing this makes a useful difference.

What is important, I think, is that the Exerfly AND the other high-intensity efforts supported each other.

There certainly is one difference that the Exerfly provided – heavy eccentric load, which is the physiological basis for using a flywheel. So not only could I maintain high-intensity efforts during this time, but there was also regular heavy eccentric loading – something that would not have been possible otherwise.

You could argue that even if I had returned to the gym earlier, the eccentric loading I would have experienced would have been less due to the limitations on eccentric load when utilising traditional weight training.

From a psychological standpoint, equipment that allowed me to utilize heavy loads and 'feel strong' kept sessions interesting and provided motivation for completing sessions at home when there was lots of change – a classic time for training to cease.

What I find very interesting is that lower body strength levels were maintained, despite not having access to the platform after November. Between January and March, I relied on the rack mount for heavy external load exercises that primarily involved the upper body (the rack mount lends itself to the upper body and accessory work).

Increases in max strength are specific but not isolated to the area used, so in theory, doing upper body max strength will positively affect other areas of the body.

Again though, I firmly believe it was the Exerfly itself that made the difference. When doing UB exercises in a standing position, the high levels of eccentric overload mean that the lower body contributes significantly to performing each rep by providing a strong base to execute the movement from and staying in control of the eccentric overload.

This last point is critical in performing each rep with max intent, in turn keeping eccentric forces high.

The Exerfly provides tremendous value and utility as part of a home gym. A small footprint, easy setup, and lightweight make it great for saving space and transportation – so it can be taken to the gym and connected to a rack; to the local park and tied to a tree; o used in platform mode in a speed and power session.

In an athletic setting, it can be crucial in maintaining performance. High levels of max strength and power can be maintained, but training could be streamlined and consistent – no relying on hotel gyms or squeezing in around classes at the local gym. Training efficiency can also be improved with strength sessions completed at the same location as field sessions, eliminating the need for travel between locations.