Flywheel resistance training calls for greater eccentric muscle activation than weight training

Introduction

Skeletal muscle inherently possesses greater mechanical efficiency and ability to generate force in lengthening (ECC) than shortening (CON) actions. Therefore, the electromyographic (EMG) amplitude is less while lowering (ECC) than lifting (CON) weights.

Thus, the metabolic demand is less when lowering (ECC) than lifting (CON) weights. It seems that more load is placed upon each active muscle fiber in the ECC action, which partly explains the more significant hypertrophy reported following chronic resistance training comprising coupled ECC and CON actions or ECC actions compared with CON actions only.

This study looked at changes in muscle activation and performance in healthy men in response to 5 weeks of resistance training with or without "eccentric overload."

What They Did

Seventeen healthy men performed 5 weeks of unilateral knee extensor training of the left limb. Subjects were assigned to 12 flywheel (Group A) or standard weight stack (Group B) resistance exercise sessions. Each session consisted of four sets of either seven maximal repetitions (Group A) or seven RM (repetition maximum; Group B) performed two to three times per week.

- The left limb's strength and root mean square EMG (EMGRMS) and rate of force development (RFD) were determined during maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) and training mode-specific coupled CON–ECC actions pre-and post-training.

- Root mean square electromyographic (EMGRMS) activity of mm. vastus lateralis and medialis was assessed during MVC and used to normalize EMG RMS for training mode-specifIc concentric (EMGCON) and eccentric (EMGECC) actions at 90°, 120° and 150° knee joint angles.

What They Found

Group A showed greater overall normalized angle-specific EMGECC of vasti muscles than Group B. Group A showed near-maximal normalized EMGCON both pre-and post-training. EMGCON for Group B was near-maximal only post-training. While RFD was unchanged following training (p > 0.05), MVC and train- ing-speciFIc strength increased (p < 0.05) in both groups.

The study's main finding was the markedly greater EMG, particularly EMG ECC activity, during flywheel compared with weight stack resistance exercise before and after training. Hence, the greater muscle activation and the resulting mechanical stress using a flywheel may explain the very robust muscle hypertrophy reported earlier in response to 5 weeks of flywheel resistance training.

Practical Application

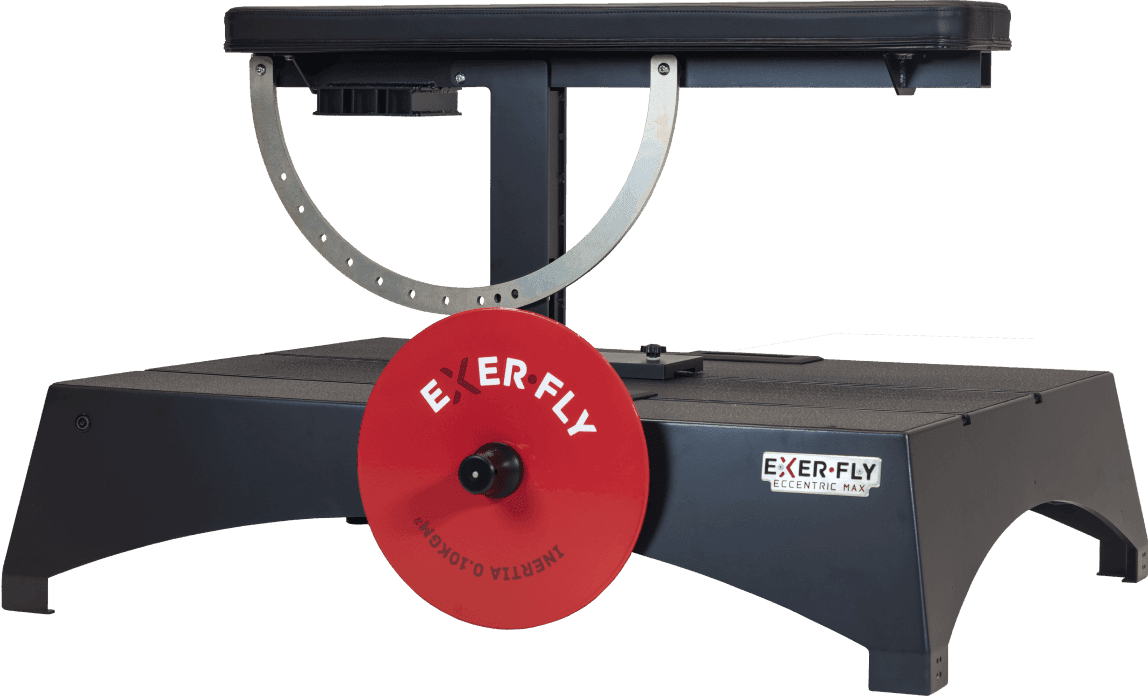

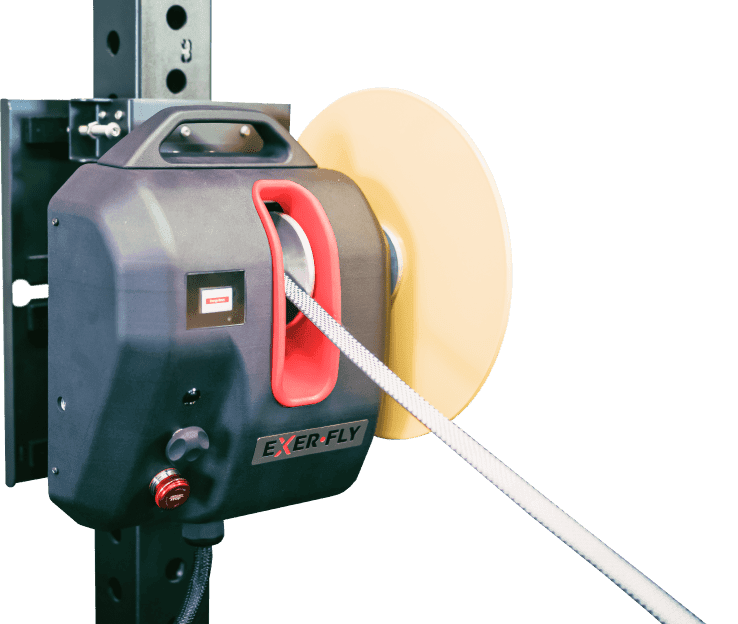

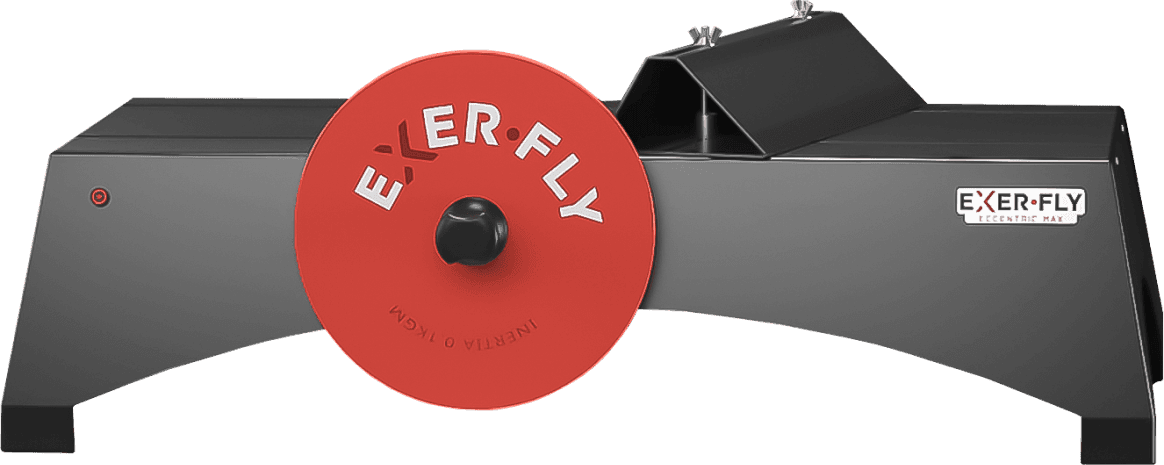

The higher EMG ECC activity noted with flywheel exercise compared to standard weight lifting can be attributed to its unique iso-inertial loading features, resulting in greater mechanical stress, which may explain the robust muscle hypertrophy reported earlier in response to flywheel resistance training.

Reference