Functional and Muscle-Size Effects of Flywheel Resistance Training with Eccentric-Overload in Professional Handball Players

Introduction

Muscle strength and power are imperative in competitive team sports such as handball. These allow athletes to carry out specific actions that determine performance (i.e., throwing, jumping, running, and hitting). In these sports, players must repeatedly carry out short, explosive efforts such as accelerations and decelerations during sprints with changes of direction.

Handball involves high-intensity, short-duration exercise, requiring a well-developed aerobic fitness, speed, and strength. So, new training methods are being pursued to improve the ability of skeletal muscles to develop explosive strength. Common exercises for explosive-strength improvement include plyometrics, ballistic exercises, and weightlifting.

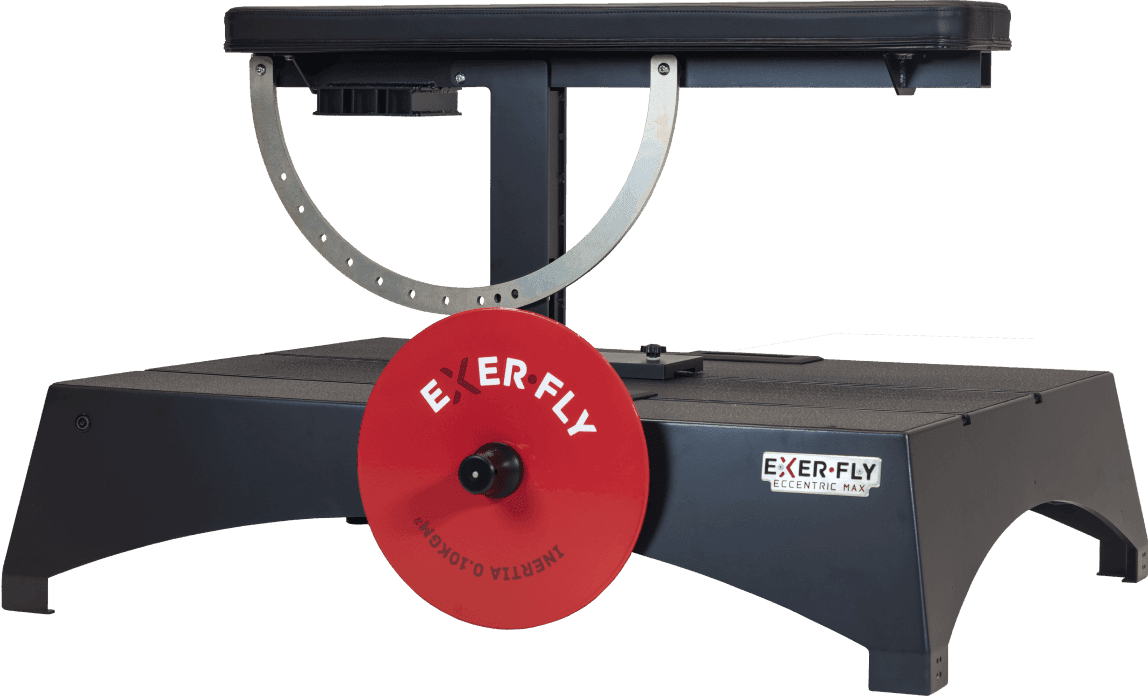

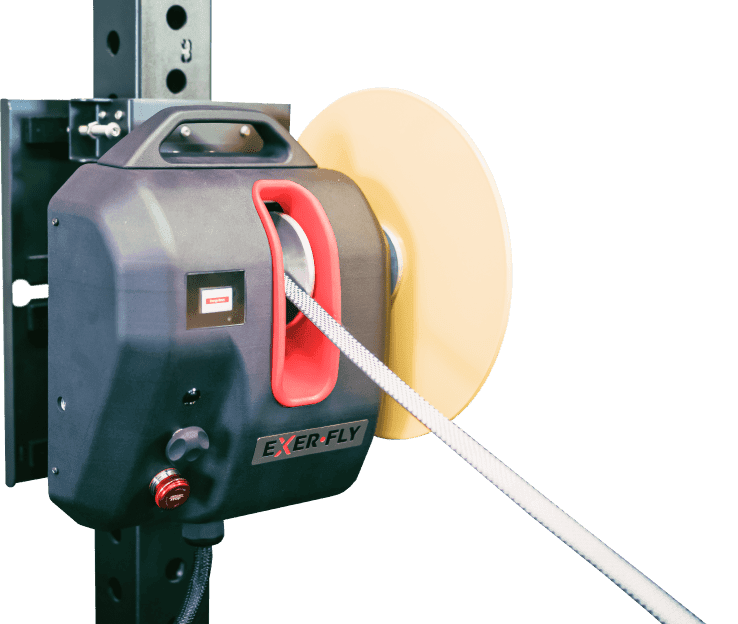

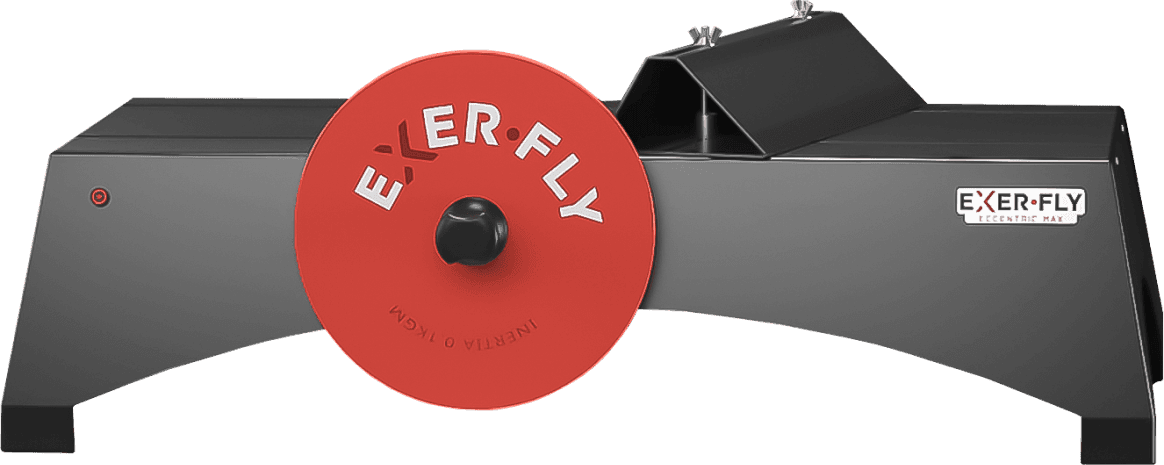

As an alternative to these traditional methods, inertial-resistance training emerges as a method applied through different systems, such as flywheel devices. Flywheel devices provide a gravity-independent stimulus that causes greater muscle activation and allows for brief episodes of eccentric overload. This study looked at the effects of 6 weeks (15 sessions) of flywheel resistance training with eccentric overload on different functional and anatomical variables in professional handball players.

What They Did

29 athletes were randomly divided into two groups.

- Group A carried out 15 sessions of flywheel resistance training with eccentric-overload in the leg-press exercise, with 4 sets of 7 repetitions at a maximum-concentric effort.

- Group B performed the same number of training sessions, including 4 sets of 7 maximum repetitions using a weight-stack leg-press machine.

Their regular weekly exercise practice consisted of 4 handball sessions (~9 h), 3 sessions including strength/power exercises, 3 on-track specific physical training sessions (changes of direction and plyometric exercises), and 1 competitive match (at the weekends).

The participants were highly experienced with free-weight resistance exercises, but none had previously used flywheel devices.

The results measured included maximal dynamic strength (1RM), muscle power at different submaximal loads (PO), vertical jump height (CMJ and SJ), 20 m sprint time (20 m), T-test time (T-test), and Vastus-Lateralis muscle (VL) thickness.

What They Found

The results of Group A showed a significantly better improvement in PO, CMJ, 20 m, T-test and VL, compared to Group B. Additionally, athletes from Group A showed significant improvements concerning all the variables measured:

- 1RM (ES = 0.72)

- PO (ES = 0.42 - 0.83)

- CMJ (ES = 0.61)

- SJ (ES = 0.54)

- 20 m (ES = 1.45)

- T-test (ES = 1.44)

- VL (ES = 0.63 - 1.64).

Practical Application

Handball requires repeated short, explosive efforts such as accelerations and decelerations during sprints with changes of direction. This study suggests that flywheel resistance training with eccentric overload affects functional and anatomical changes in a way that improves performance in well-trained professional handball players.

Reference